FAMACHA: An Eye-Colour Based Ready Reckoner for Assessing Worm-load in Small Ruminants

Nov 27, 2014

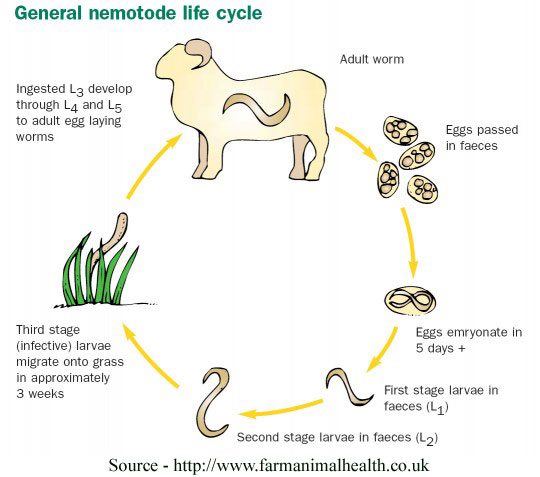

Gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) infections, or worms1, are an important cause of low productivity in small ruminants. The usual practice of administering anthelmintics involves drenching2 of goat and sheep two to three times a year. This has resulted in the development of anthelmintic resistant strains of parasites and thus limited effectiveness of worm control programmes.

In order to minimize worm resistance, it is essential to develop alternative ways of managing nematode infections. Research suggests that strategies which do not rely heavily on chemical treatment of entire flocks or herds are a better approach3. One possibility is the use of clinical anaemia as a determinant, with subsequent selection and de-worming of only those animals which seem unable to cope with the infection.

About the FAMACHA system

The FAMACHA (FAffaMAlanCHArt) system, developed in South Africa by Dr Francois "Faffa" Malan is about the assessment of worm burden4 in livestock and the need for treatment.

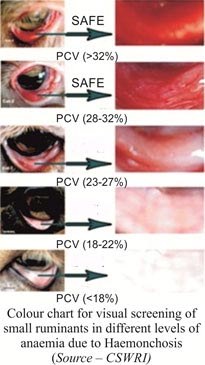

FAMACHA based deworming is a low-cost, low-tech, targeted selective treatment (TST) method, which refers to the identification and treatment of only those individual animals that require supportive treatment, while leaving the rest untreated. This system helps in categorizing the anaemic status of goats and sheep based on the conjunctivae5 colours on a scale from 1 (red/non-anaemic) of healthy animal through shades of pink to 5 (white/severely anaemic) of an unhealthy animal. The anthelmintic treatment is recommended for livestock categorized in groups 4 and 5 only while the animals falling in categories 1 to 3 are considered normal. According to the FAMACHA system, the colour of the conjunctiva of each animal is classified into five categories listed in the following table. The table also lists the treatment guidelines based on the colour of the conjunctiva:treatment.

| Clinical Category | Colour of Conjunctiva | Treatment Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | No |

| 2 | Pinkish-red | No |

| 3 | Pink | May be |

| 4 | Pinkish-white | Yes |

| 5 | White | Yes |

Source - http://www.sheep101.info/201/parasite.html

The experiment which led to the development of the first FAMACHA card was conducted on a sheep farm near Badplaas, South Africa6, in a climatic zone characterized by hot, wet summers and mild winters. Later, the system was tested with indigenous goats in South Africa , and subsequently tested and adopted in several other countries, including Brazil, Morocco, Kenya, Italy, Switzerland and India7.

According to Vatta8 the use of a selective treatment strategy is founded on the concept that parasites are not equally distributed in host populations. It is generally 20-30 per cent of the animals that harbour most of the worms and are responsible for most of the eggs deposited in the faeces on the pasture and, if, this group of animals can be identified and treated, this will greatly reduce the daily pasture contamination. Vatta also observed that the range of colours in conjunctivae is smaller in goats than sheep, making the application of the FAMACHA system more difficult in the case of goats; further testing is required to validate efficacy of use of the system in goats.

_____________________________________________________________________________

CSWRI Case study9

About CSWRI

The Central Sheep and Wool Research Institute (CSWRI) at Avikanagar, Rajasthan, a member institution of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), is engaged in research, training and extension activities on sheep and rabbits. CSWRI undertook an experiment in introducing the modified worm management technology for sheep, by adoption of the FAMACHA system, which not only delays the emergence of anthelmintic resistance, but also decreases the cost of worm control.

The experiment

To address the problem of anthelmintic resistance, CSWRI developed a region-based worm management programme based on real time epidemiology of parasites; for example, taking into consideration their reproductive and grazing practices in addition to the climatic conditions. This worm management programme included the following protocol:

- one strategic drench10 during mid to late monsoon season

- one need based tactical drench11 during autumn/winter

- Use of anthelmintic drugs on rotation basis between the broad (benzimidazole and levamisole) and narrow (salicylanilide and levamisole) spectrum group unlike earlier where only two broad spectrum group of drugs were used every time.

Results

Faecal examination of both field and farm based herds revealed that, even during a worm favourable monsoon season almost 20 to 50% of animals had very low faecal egg count, and did not require anthelmintic treatment. This is in contrast to the normal practice where the anthelmintic drug is administered to all the sheep in a herd, resulting not only in high cost of drug and drenching, but also contributing to the emergence of anthelmintic resistant strains of nematodes.

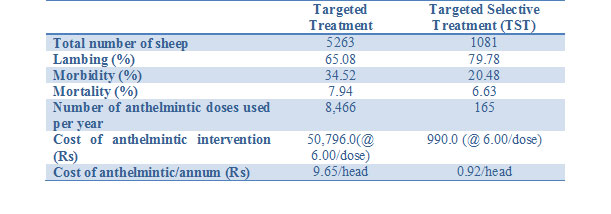

Based on FAMACHA assessment, only 23 percent of the average sheep in the flock, falling in categories 4 and 5, needed to be dewormed/ drenched per year through the TST, as opposed to 100 percent in the conventional approach.

CSWRI established that the FAMACHA based deworming programme saved Rs 12 per sheep per annum, compared to the conventional drench schedule, without compromising on productivity of the flock. The comparative evaluation of conventional (2-3 drench/annum) and modified technology (one drench/annum) in worm infected sheep yielded a net gain of Rs 100.57 per sheep per annum. In addition to the direct financial gains, some of the indirect benefits included reduction in selection pressure on parasites; delay in the emergence of anthelmintic resistance in parasites through maintaining population in refugia12; extended efficacy of existing anthelmintic treatments, and reduced labour costs.

Because of the simplicity of the process, it was easy for semi-literate farmers in rural areas to adopt and implement the targeted selective treatment in their herds. After the success achieved in on-farm research, CSWRI undertook field level tests to understand and establish the efficacy of this method in field conditions.

CSWRI’s survey revealed that after adoption of the TST method, a marked reduction in the mortality rate of sheep was observed. It has also led to an increase in sheep productivity in terms of body weight, regular kidding and improved reproductive performance. The following table shows the comparative performance for targeted treatment and targeted selective treatment approaches for worm control in organized sheep farm in arid Rajasthan13.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Advantages

Research undertaken by Jan A. Van Wyk14(2002), suggests that the FAMACHA system can be effectively implemented by small holder livestock rearers even with low literacy levels. Further, application of FAMACHA tool leads to a large reduction in anthelmintic use as compared with conventional drenching approaches and slows down the development of anthelmintic resistance. According to a research study, there were 0.57 doses of anthelmintics administered per doe in the FAMACHA group compared with 3 doses per doe in the controls15. The FAMACHA system may be also used to identify more susceptible animals, and take appropriate remedial measures.

Drawbacks

Jan A. Van Wyk (2002) also identifies some challenges meted out during the application of the FAMACHA system. These include incorrect diagnosis by farmers, as the symptoms of bluetongue disease, pasteurellosis or pulpy kidney disease can be wrongfully ascribed to endoparasitic load; the complacence of farmers to score the sheep based on the eye colour, without reference to the FAMACHA card for calibration, and lack of regularity (long intervening periods) in examining the livestock. The study establishes that the livestock rearers must be adequately trained and sensitized to be able to use the FAMACHA system effectively.

Recommendations

Some of the recommendations for use of the FAMACHA system are listed as follows:

- Examine the animals at least every 2-3 weeks at the beginning of the expected period of occurrence of nematode infections. During the critical periods however the animals must be examined on a weekly basis16.

- Adult animals with good health and body condition must be treated for the 4th and 5th scale only. However, in case of animals that are not in good health, treatment must be provided at the 3rd scale itself.

- Anorexic and weaker looking livestock and the ones with a submandibular oedema (bottle jaw condition)17 must be specifically identified and provided treatment.

- If the number of anaemic animals in a flock or herd is greater than 10%, the animals in the 3rd scale must also be treated. It is also advisable to change the pasture used by anaemic flock.

- Animals should be observed in direct sunlight and matched to the chart, which should always be used for matching colours. If the animal's eye colour is in between two chips, score as the lighter chip (higher number).

- Pregnant animals, lactating animals and animals under a year of age should be dewormed when they are in stage 3 as their immune system is not fully functional. Additionally, animals with bottle jaw (swelling under the chin) should be dewormed.

The following video displays the use of FAMACHA score card to score small ruminants: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BAdeVez5yyc

Reviewed by – Dr T. Vijayakumar, Joint Commissioner, Meat and Pig, Department of Animal Husbandry

Contributed by – Ruchita Khurana with inputs from SA PPLPP Coordination Team

Suggested Citation - SA PPLPP (2014), “FAMACHA: An Eye-Colour Based Ready Reckoner for Assessing Worm-load in Small Ruminants”. Case Study, New Delhi, India

References

- The main parasites found in the stomach of sheep and goats are Brown stomach worm (Ostertagia spp.), Stomach hair worm or bankrupt worm (Trichostrongylus axei) and Stomach worm, wire worm, twisted barber-pole worm (Haemonchus contortus). (Source - www.moredun.org.uk and www.infovets.com)

- Drenching is administering a large oral dose of liquid medicine to an animal, by pouring down the throat.

- Waller, Peter J. (2003). Global perspectives on nematode parasite control in ruminant livestock: the need to adopt alternatives to chemotherapy, with emphasis on biological control. Animal Health Research Reviews, 4, pp 35-44.

- The number of worms carried by an individual host.

- The mucous membrane that lines the inner surface of the eyelids and the exposed surface of the eyeball.

- Vatta, Adriano.F. et al (2007): Benefits of urea-molasses block supplementation and symptomatic and tactical anthelmintic treatments of communally grazed indigenous goats in the Bulwer area, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, Journal of South African Veterinary Association, 78(2): pp81–89

- Singh D. and Swarnkar C.P.(2012): Evaluation of targeted selective treatment strategy in sheep farm in Rajasthan, Indian Journal of Animal Sciences

- Vatta, Adriano.F., The FAMACHA System – an aid in the management of Haemonchosis in Small Ruminants

- Ibid 7

- A strategic drench, also considered as a preventive drench, is done at critical times of the year in relation to the epidemiology of parasite infection, often in association with some form of animal management. The aim is to maximize the effect thereby reducing the number of treatments required to achieve effective control. (Source: http://www.ancare.com.au)

- A tactical drench however is a curative drench given when there is a visual evidence of a parasite effect. (Source: http://www.asap.asn.au)

- The academic definition of refugia is ‘the proportion of a worm population that cycles (breeds) and is not exposed to a particular drench chemical, so escapes genetic selection for resistance’. If one keeps on drenching, the susceptible worms will die and the resistant ones will survive and breed. So we need to keep a population of ‘susceptibles’ in the system somewhere, to keep on breeding with non-susceptibles which will then be killed by drench.

- Ibid 7.

- Wyk, Jan A. And Bath, Gareth F. (2002), The FAMACHA system for managing haemonchosis in sheep and goats by clinically identifying individual animals for treatment, Veterinary Research, 33

- Mahieu, M.(2007), Evaluation of targeted drenching using Famacha© method in Creole goat: Reduction of anthelmintic use, and effects on kid production and pasture contamination: Veterinary Parasitology, 146(1–2): pp135–147

- R.M. Kaplan et al.(2004), Validation of the FAMACHA© eye color chart for detecting clinical anemia in sheep and goats on farms in the southern United States, Veterinary Parasitology 123, pp105–120

- Also called as bottle jaw, this health condition is caused by the swelling in the lower mandible region or the lower jaw due to inflammation of salivary glands.