Community-led Initiatives for Conservation of the native Bhagli (Sonadi) Sheep, District Pali, Rajasthan – the story of Dharmaram Raika

Jul 16, 2013

Dharmram Raika receiving the Breed Saviour Award from Dr. B. L. Joshi, Director, NBAGR, at the Award Ceremony at Karnal in March 2013

Dharmaram Raika is a landless shepherd from Bijapur village, in the Bali tehsil of district Pali in Rajasthan. Dharmaram belongs to the Raika community – the indigenous pastoral community of Rajasthan. He rears a flock of 30 Bhagli sheep (a local name for the Sonadi1 breed of sheep) comprising three rams and 27 ewes. In addition to Dharmaram, there are 35 - 40 households in his village who also rear the Bhagli sheep. For Dharmaram and his family, sheep rearing is a traditional livelihood activity. His family has owned and reared sheep for as long as he can remember though the flock size has now greatly diminished on account of a reduction in grazing lands and difficulties in accessing drinking water. The Bhagli sheep breed is originally from Madhya Pradesh and was brought to Rajasthan by migratory shepherds including the Raikas. The Bhagli sheep, meaning ‘of good fortune’ in the local dialect, is medium to large in size, with long broad ears and a relatively large head. The Raika value this breed for its high milk and meat production2.

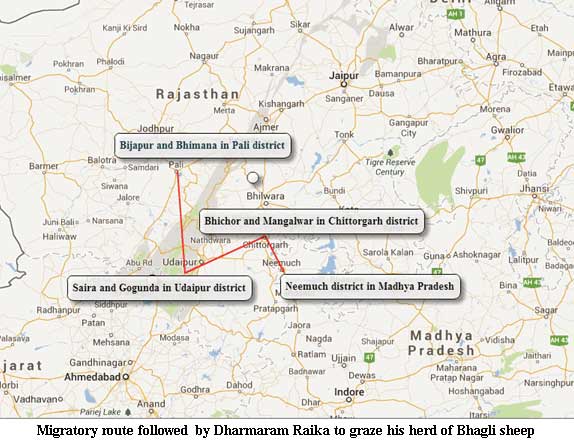

Together with other shepherds of the village, Dharmaram and his family migrate with their sheep flock for eight months each year to Neemuch in Madhya Pradesh. The migratory route passes through the Bijapur and Bhimana villages in Pali district, to Saira and Gogunda in Udaipur district and then through Bhichor and Mangalwar in the Chittorgarh districts of Rajasthan before entering Neemuch district in Madhya Pradesh. This is a traditional grazing route followed by shepherds. The sheep graze both in forests and farm lands along these routes. The practice is to fan out in different directions along with their sheep flock during the day and get together at night at a common spot generally decided by the patel (headman) of the shepherd group. This practice minimizes crowding in a particular area ensuring that there is enough fodder for all the sheep.

Together with other shepherds of the village, Dharmaram and his family migrate with their sheep flock for eight months each year to Neemuch in Madhya Pradesh. The migratory route passes through the Bijapur and Bhimana villages in Pali district, to Saira and Gogunda in Udaipur district and then through Bhichor and Mangalwar in the Chittorgarh districts of Rajasthan before entering Neemuch district in Madhya Pradesh. This is a traditional grazing route followed by shepherds. The sheep graze both in forests and farm lands along these routes. The practice is to fan out in different directions along with their sheep flock during the day and get together at night at a common spot generally decided by the patel (headman) of the shepherd group. This practice minimizes crowding in a particular area ensuring that there is enough fodder for all the sheep.

Dharmaram informed that while some farmers consider migratory shepherd flocks as a threat to their farmlands, a few others value their stay because of the sheep droppings and the resultant positive impact on soil fertility and crop growth. In addition to providing the shepherds’ groups (7-8 families) with 30-50 kg of wheat for each night that the flock is herded on their land, farmers also provide them with 250 gms of tea and a kg of sugar. The shepherds stay on these farms for a maximum of 1-3 days depending upon the availability of fodder in the surrounding areas. The shepherds return to their native villages during the four monsoon months from June to September each year. Traversing the entire route on foot both for the onward as well as the return journey was earlier the norm, but with increased agriculture and a reduction in fallow lands along the way, as also restrictions on grazing, sheep are now herded on to trucks for the journey back home as the monsoon commences.

Earlier the price of sheep wool was fixed on a per sheep basis, in consultation with the trader who was willing to buy it. For example a rate of Rs 16-20 / sheep was fixed irrespective of the amount of wool from each sheep which averaged 1 to 1 ½ kg. Additionally, there was no direct cost of shearing. The shepherds provided shearers with two meals3 and tea in return. Now, however, it is the shearers who collect the wool as fee for their shearing services, and shepherds are not paid for the wool.

Dharmaram informed that there are no veterinary facilities close to their village. Raikas have a good knowledge of ethno-veterinary practices and also frequently de-worm their sheep, particularly when they notice a reduction in appetite. The de-wormer is bought from a drug-store for Rs 500 and is sufficient to de-worm 100 animals. Preventive vaccination is rarely undertaken. Among other common diseases, are skin diseases for which the shepherds stock common medicines for topical application.

The Raika shepherd community in Dharmaram’s village has organized themselves into a herding group called ‘Dang’ comprising of eight 'Dolris4' of 4-5 households each. The Dang is governed by rules, set by the community to ensure the equitable sharing of costs and income. For example, a Raika who owns less than 50 sheep will receive Rs 8,000 for eight months from someone who owns 200 sheep as labour costs for grazing his animals. Dharmaram is presently the representative of his Dang which has 4,000 Bhagli sheep. The entire group moves together comprising of their families, 4,000 sheep, 100 goats (reared for milk), 14 camels and 22 donkeys for carrying utensils and other household goods.

Lambs are sold for Rs 1,500-2,000 while a one year old sheep is sold for Rs 5,000-6,000. Based on the height and weight attained by lambs in 3-4 months time, the healthy lambs are retained to increase the flock size while the remaining are sold to traders. Selling of young lambs is a preferred practice to reduce the spread of disease and associated risks.

For a herd of 100 ewes, there are around 10-20 rams. The sheep are primarily reared on grazing, though breeding rams are given sesame oil three to four times a year in addition to eggs. Pregnant ewes are also sometimes fed on ghee mixed with milk. A lot of care is taken to prevent in-breeding among sheep to ensure good progeny and health. The rams are, therefore, exchanged with those belonging to shepherds of a different dolri after the breeding cycle.

Despite taking turns in watching-over their herds at night, theft is the most common problem faced by Raika shepherds, leading to huge losses along the migratory route. However, these constraints have not deterred Dharmaram who is keen to continue his traditional livelihood activity of sheep rearing. The increasing reduction in grazing lands is a major constraint, and Dharmaram shared his experience of 2010 when their herding group protested against the ban on entry to the Kumbhalgarh forests, which had been declared a wildlife sanctuary. After much negotiation the forest department had agreed to charge Rs 11 per pair of sheep for grazing in the forests.

Dharmaram informed that the Raika shepherds have a close association with the Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan (LPPS)5, an NGO working in the region for the welfare of livestock rearing communities. LPPS facilitates procurement of medicines as also provides training on improved management practices for sheep rearing.

Dharmaram has four children – two sons and two daughters. While his oldest son, who has completed higher secondary education, is employed as a helper in a chemist shop in Mumbai, the other three children are studying, but are not keen to take up sheep rearing. Dharmaram is concerned at the future of pastoralism, and in particular feels that efforts should be made to facilitate access to health care services.

Under the Breed Saviour Awards 2012, instituted by the National Bio-diversity Authority, the LIFE Network and the National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, Dharmaram has been awarded for his efforts to protect and conserve the Bhagli sheep breed. The award consists of a certificate and a cash prize of Rs 10,000. Dharmaram has shared the prize money with the other four members of his dolri. “I had never imagined that our work with conserving and raising Bhagli sheep will be so recognized to earn us an award. The Bhagli brought us fortune, as its name”, says Dharmaram.

References

1. The Sonadi breed is found in the Mewar region of Rajasthan comprising Udaipur, Dungarpur, Chittorgarh and Banswara districts. They are also known locally as Laapdi (long flat drooping ears) and Bhagli (of good fortune). For more information about this breed visit the link: #

2. Sheep Husbandry and Ethnoveterinary Knowledge of Raika sheep pastoralists in Rajasthan, India, by Ellen Geerlings (http://www.pastoralpeoples.org/docs/egfull.pdf)

3. One of the two meals has to be a traditional meal comprising daal, baati and churma.

4. A dolri comprises 4-5 households who share their meals and work collectively during migration. Women in the dolri are responsible for cooking, washing clothes and caring for young children, while the men take turns grazing and managing the sheep including guarding the dolri at night.

5. Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan (LPPS) is a non-profit organization set up in 1996 to support traditional pastoralist communities in Rajasthan. LPPS aims to support rural livelihoods through participatory research and community implementation of sustainable land use practices.

Contributed by - SA PPLPP Coordination Team with inputs from Sh. Khetaram Raika, Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan (LPPS), Pali, Rajasthan